Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?

Year: 1989

Runtime: 144 mins

Language: Korean

Director: Bae Yong-kyun

About three monks in a remote monastery; an aging master, a small orphan and a young man who left his city life to seek Enlightenment.

Warning: spoilers below!

Haven’t seen Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? yet? This summary contains major spoilers. Bookmark the page, watch the movie, and come back for the full breakdown. If you're ready, scroll on and relive the story!

Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? (1989) – Full Plot Summary & Ending Explained

Read the complete plot breakdown of Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? (1989), including all key story events, major twists, and the ending explained in detail. Discover what really happened—and what it all means.

Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? is a contemplative film that invites quiet reflection on life, death, and the elusive nature of enlightenment through the lens of Seon Buddhism. Centered on three interconnected figures—a young orphaned boy, a novice monk, and an elderly monk—the story unfolds at a remote mountainside monastery where practice, doubt, and compassion collide in patient, often stark ways. The film’s title alludes to Bodhidharma, the legendary sixth-century monk who is said to have transmitted Zen to China, and while the film doesn’t spell out the reference in a literal way, its themes echo that lineage of hard-won insight. The protagonists are Hae-jin, a child whose life has already begun to hinge on resilience; Ki-bong, a young monk who has chosen cloistered life in pursuit of peace; and Hye-gok, the venerable master whose years of practice have led him to question the very value of knowledge and external achievement.

From the outset, the film anchors its inquiry in two hwadu, or Buddhist riddles, which never yield easy answers. The first is: What was my original face before my father and mother were conceived? The second asks, in the moment of enlightenment or death, where does the master of my being go? The elderly master disciplines Ki-bong with these enigmatic prompts, asking him to “hold the hwadu between his teeth” as a test of endurance, concentration, and the willingness to travel into a sense of self that is not tied to ordinary identity. The old man’s method, and his insistence that true understanding may arise only when one lets go of learned knowledge, moves the young monk to confront his own desire for a different life: to escape hardship, to find a form of peace that may require a more intimate engagement with the messy, imperfect world he once left behind.

In parallel, the film sketches a small, intimate world around Hae-jin. The boy’s act of compassion—injuring a bird while bathing, and then attempting to nurse it back to health—begins a thread about attachment, responsibility, and the consequences of even well-meaning action. When the bird’s mate lingers nearby, the scene becomes a meditation on presence and loss, foreshadowing the lessons about impermanence that will unfold later. The sequence shifts abruptly to the image of an ox breaking free into the forest, a motif that reappears as a counterpoint to human striving and the natural order of things.

Ki-bong’s journey toward the elder master’s mountain retreat is framed by a conflict between renunciation and duty. He has left a life of hardship in search of inner peace, yet his path intersects with a duty to heal the master, to gather alms, and to care for his own blind mother Ki-bong’s mother who is struggling to manage on her own. The film uses these simple acts—a purchase of medicine with alms money, a visit to his mother, a return to the monastery—to reveal a character who discovers that spiritual growth cannot be achieved in isolation from the very people who shape one’s life.

As Ki-bong returns to the monastery, the master’s illness deepens. The old man does not forbid Ki-bong from leaving; instead, he tests whether the young monk can return to human ties and still keep faith with the vow he has made to serve. When Ki-bong attempts to rejoin society, a flash flood nearly claims his life, and it is Hae-jin who helps rescue him, underscoring a shared interdependence that runs through all the film’s relationships. The recovery is not simply physical; it is spiritual. The master, meanwhile, has been meditating through the crisis, and Ki-bong learns that the old man has “traded his life” to save him, a revelation that compels the younger man to accept a heavy, moving obligation: to perform the last rites and to ensure the master’s body is burned on the hill so that the master can return to his original place.

A culmination arrives at a full-moon festival, where the line between worldly life and the spiritual journey becomes poetically blurred. The festival dance is revealed to be performed by the same elderly monk in another form—the dancer is, in truth, the master who has taken a living, visible shape for a moment of ceremony. Returning to the monastery after this revelation, Ki-bong finds that the master has died. In accordance with the elder’s last wish, Ki-bong carries the coffin up the hill and begins the difficult pyre, relying on paraffin that the master had hinted at earlier. A light drizzle complicates the burn, and Ki-bong retrieves the remaining fuel to complete the rite. He spends the night at the funeral site, grappling with a raw, honest sense of grief that gradually gives way to clarity about death, devotion, and the kind of peace that lies beyond fear and desire.

After the pyre burns, Ki-bong discovers the master’s bones in the ashes. He grinds these bones into powder and scatters them across water, earth, trees, and plants—an act that symbolically returns the master to the world he had sought to commune with, and which the youth had at first left behind. By reuniting the body with the land, Ki-bong achieves a form of closure and, in the process, the film suggests, perhaps, a genuine comprehension of the hwadu’s second question: where does the master go in death? The young monk returns to the monastery, bearing the weight of his learning and promising to tend to the master’s remaining possessions, before stepping away from the life he once sought to escape. His resolution is not a rejection of the world but a deeper embrace of it.

In the film’s final sequence, the younger generation asserts its own form of initiation. The boy Hae-jin comes of age in the cinema’s most intimate moment of transformation: he reenacts the night’s events in a small play, burning the master’s remaining effects in miniature to honor his teacher’s teachings. He then steps toward the stream for water, the bird’s former companion continuing to chirp as if to remind him of what he has learned: impermanence. The conclusion binds together the images of the dead master, the ash and bones returned to the earth, the dancing girl whose life and form illuminate the festival, and the ox that reappears at dawn with a man walking beside it in sunlight—an emblem of continuity, renewal, and the possibility that enlightenment can be found not by escaping life’s messiness but by embracing it with a steady, compassionate heart.

In the end, the film offers a rare, spare vision of awakening: a young boy and a departing monk, a living world that holds both beauty and suffering, and a practice that invites us to listen for a voice beyond words. The journey is not about reaching a final summit, but about learning to inhabit the present moment with patience, humility, and grace. The characters’ names may be their own, but the story belongs to everyone who seeks a steadier, more compassionate way of being in the world. The film’s quiet power lies in its insistence that true peace is born from reverent attention to life as it unfolds—even when that life is imperfect, fragile, and deeply human.

Last Updated: October 09, 2025 at 14:32

Explore Movie Threads

Discover curated groups of movies connected by mood, themes, and story style. Browse collections built around emotion, atmosphere, and narrative focus to easily find films that match what you feel like watching right now.

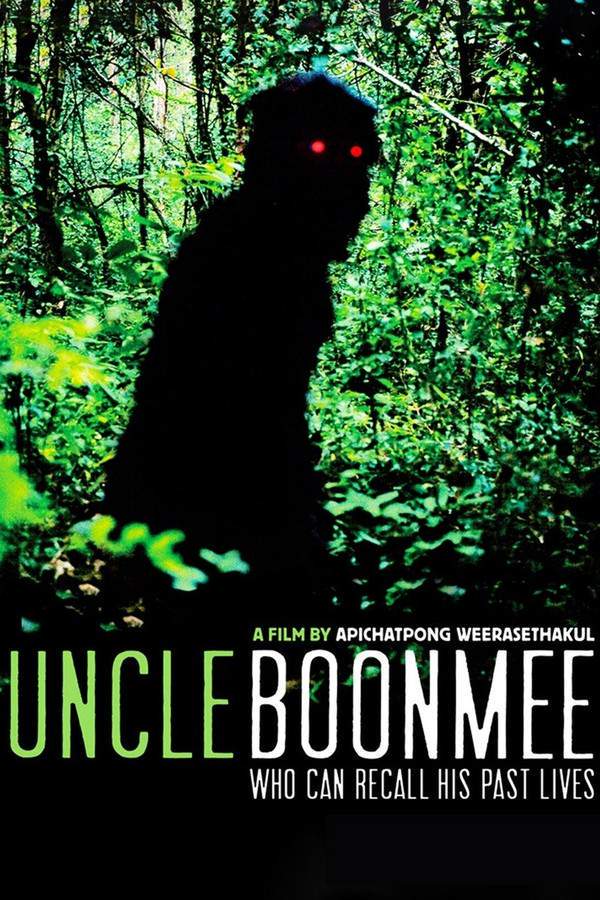

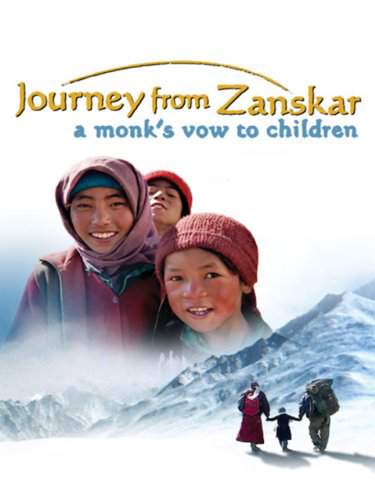

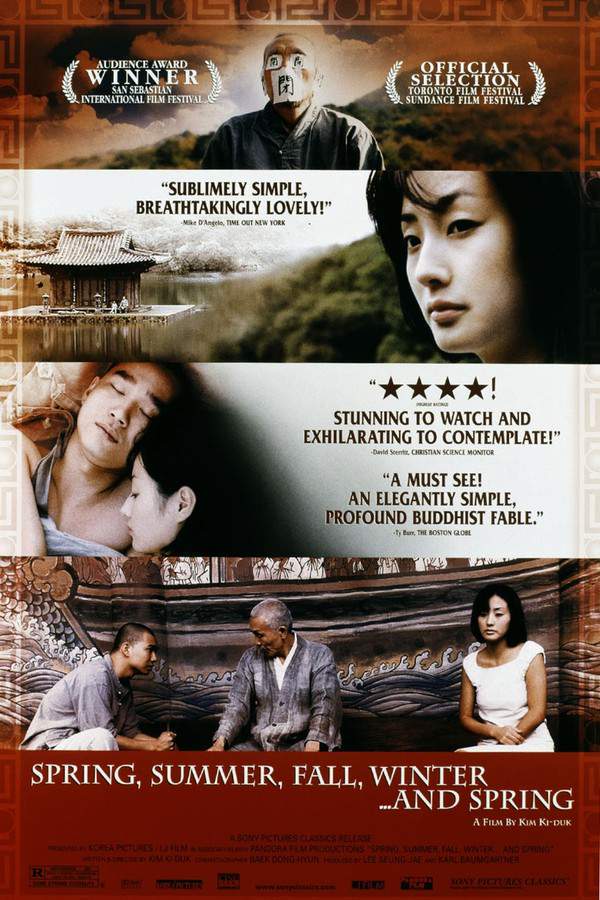

Movies of quiet spiritual journeys like Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?

Slow-paced meditations on enlightenment, monastic life, and the search for meaning.If you liked the meditative, patient exploration of enlightenment in Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?, you'll find similar films here. This thread gathers movies that focus on monastic life, spiritual seeking, and deep philosophical inquiry, all told with a serene and contemplative pace.

Narrative Summary

Narratives in this thread are driven by a character's internal quest for understanding, often involving a mentor-student relationship. The plot is minimalist, with pivotal moments occurring in quiet realizations or subtle interactions rather than dramatic events. The journey is cyclical and reflective, mirroring the process of spiritual practice itself.

Why These Movies?

These movies are grouped by their shared commitment to a quiet, reverent tone, a slow and deliberate pacing that allows for introspection, and a central focus on themes of enlightenment, duty, and the nature of existence. They create a specific, immersive mood of thoughtful serenity.

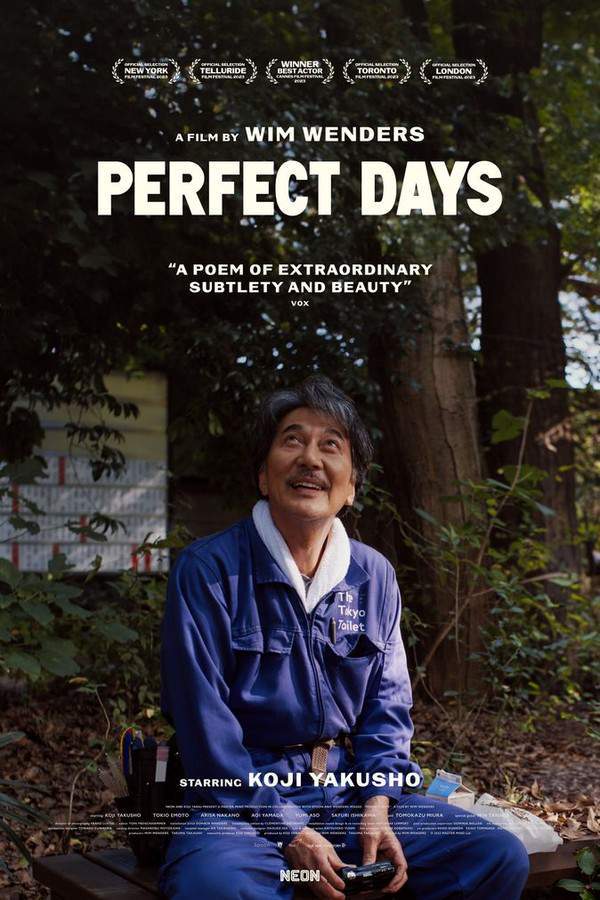

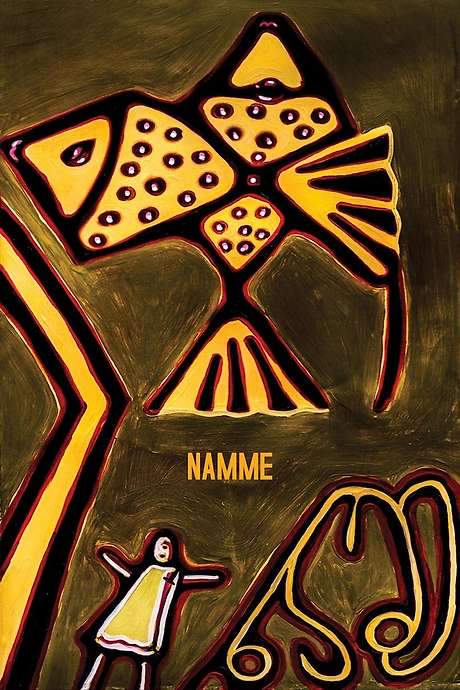

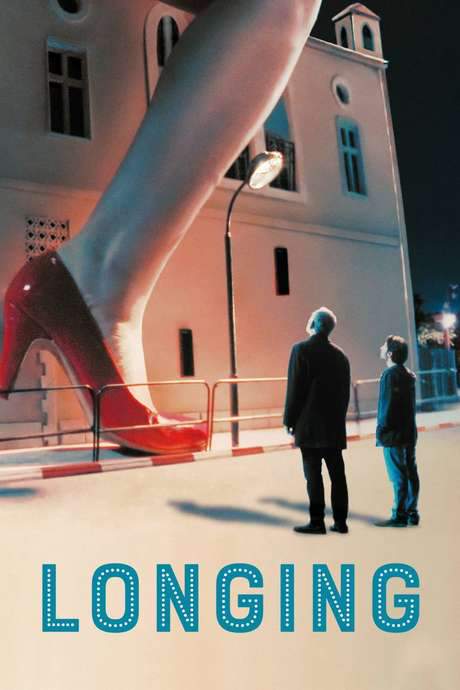

Films about life and impermanence like Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?

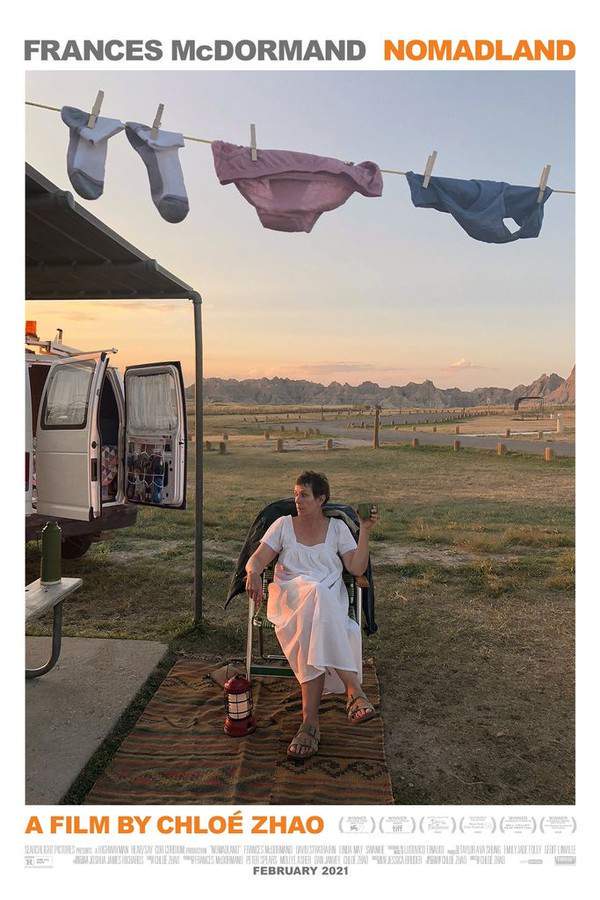

Stories that find profound beauty and sorrow in the acceptance of life's transient nature.For viewers seeking movies similar to Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? that explore themes of grief, loss, and the acceptance of impermanence. These films share a bittersweet tone and a reflective pace, finding hope and peace amidst life's inevitable changes and endings.

Narrative Summary

The narrative pattern often involves characters confronting loss—of a loved one, a way of life, or their own identity—and moving through grief toward a hard-won acceptance. The conflict is internal, centered on coming to terms with reality. The ending is typically bittersweet, acknowledging pain while finding a glimmer of peace or continuity.

Why These Movies?

This grouping is defined by a shared emotional core: a melancholic yet compassionate tone, a medium emotional weight that feels deeply human, and a bittersweet ending feel. The pacing is often slow to moderate, allowing the emotional impact to settle and resonate.

Unlock the Full Story of Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?

Don't stop at just watching — explore Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? in full detail. From the complete plot summary and scene-by-scene timeline to character breakdowns, thematic analysis, and a deep dive into the ending — every page helps you truly understand what Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? is all about. Plus, discover what's next after the movie.

Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? Timeline

Track the full timeline of Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? with every major event arranged chronologically. Perfect for decoding non-linear storytelling, flashbacks, or parallel narratives with a clear scene-by-scene breakdown.

Characters, Settings & Themes in Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?

Discover the characters, locations, and core themes that shape Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?. Get insights into symbolic elements, setting significance, and deeper narrative meaning — ideal for thematic analysis and movie breakdowns.

Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? Spoiler-Free Summary

Get a quick, spoiler-free overview of Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? that covers the main plot points and key details without revealing any major twists or spoilers. Perfect for those who want to know what to expect before diving in.

More About Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?

Visit What's After the Movie to explore more about Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?: box office results, cast and crew info, production details, post-credit scenes, and external links — all in one place for movie fans and researchers.

Similar Movies to Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?

Discover movies like Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? that share similar genres, themes, and storytelling elements. Whether you’re drawn to the atmosphere, character arcs, or plot structure, these curated recommendations will help you explore more films you’ll love.

Explore More About Movie Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?

Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? (1989) Scene-by-Scene Movie Timeline

Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? (1989) Movie Characters, Themes & Settings

Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? (1989) Spoiler-Free Summary & Key Flow

Movies Like Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? – Similar Titles You’ll Enjoy

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter... and Spring (2004) Movie Recap & Themes

Himalaya (2001) Film Overview & Timeline

Buddha Wild: Monk in a Hut (2006) Full Movie Breakdown

A Boy and Sungreen (2018) Plot Summary & Ending Explained

Samsara (2001) Spoiler-Packed Plot Recap

A Buddha (2005) Movie Recap & Themes

Mandala (1981) Movie Recap & Themes

Shaolin Master and the Kid (1978) Spoiler-Packed Plot Recap

Buddha (1961) Film Overview & Timeline

Little Buddha (1993) Movie Recap & Themes

The Light of Asia (1925) Detailed Story Recap

Passage to Buddha (1993) Full Movie Breakdown

Temptation of a Monk (1993) Detailed Story Recap

Burrowing (2009) Complete Plot Breakdown

Bodo (1993) Film Overview & Timeline