Two Stage Sisters

Year: 1964

Runtime: 112 mins

Language: Chinese

Director: Xie Jin

Set in pre‑revolutionary China, two gifted girls, Chunhua and Yuehong Xing, ascend the ranks of Chinese opera. After being sold to a Shanghai troupe, the looming revolution splits their paths: Yuehong embraces radical, politically progressive performances, while Chunhua escapes the turmoil. Amid the upheaval, they struggle to preserve their friendship.

Warning: spoilers below!

Haven’t seen Two Stage Sisters yet? This summary contains major spoilers. Bookmark the page, watch the movie, and come back for the full breakdown. If you're ready, scroll on and relive the story!

Two Stage Sisters (1964) – Full Plot Summary & Ending Explained

Read the complete plot breakdown of Two Stage Sisters (1964), including all key story events, major twists, and the ending explained in detail. Discover what really happened—and what it all means.

In 1935, a runaway tongyangxi, Zhu Chunhua, Xie Fang finds refuge with an itinerant Yue Opera troupe, the Yangchun Theatre Troupe, as it travels through a Shaoxing village. The troupe’s head, A’Xin, Mao Lu, initially intends to send the girl away, but the Yue Opera teacher Xing, Qi Feng, sees her potential and takes Chunhua in as a dedicated disciple. Chunhua’s adoption by Xing underscores the limited agency women faced in pre-revolutionary China, where performance troupes offered one of the few avenues to escape entrenched patriarchal norms. Chunhua signs a deal with the troupe and becomes the performing partner (in a dan role) to the teacher’s daughter Yuehong, who performs as a xiaosheng. Yuehong, Cao Yindi, is introduced as Chunhua’s sworn sister and collaborator, a pairing that embodies a fragile bond forged in shared struggle.

Together, Chunhua and Yuehong present a united front against oppression within a society that often instrumentalized female artists. The duo’s ascent does not go unnoticed; they’re arrested by Kuomintang police after they rebuff the advances of a wealthy landlord, revealing the state’s complicity with feudal elites. The landlord, Ni, invites Chunhua and Yuehong to sing privately at his house, and his interest in Yuehong is promptly rejected by both Yuehong and her father. In a brutal display of power, Kuomintang cops seize Yuehong during a performance, and Chunhua is also detained and tied to a pillar for days of public humiliation. The sisters’ resilience is tested again when Xing and A’Xin manage to secure their release through bribes, a bitter reminder of the corruption threaded through the regime.

As the Second Sino-Japanese War intensifies, the troupe endures escalating hardship that mirrors the nation’s turmoil. In 1941, Xing dies of illness, and A’Xin sells his two best performers to Tang, a Shanghai opera theater manager, on a three-year contract—an emblematic moment that Cui reads as the commodification of female artistry under capitalism. Chunhua and Yuehong, now established stars in the city, stand at a crossroads: Chunhua remains practical and grounded, while Yuehong leans increasingly toward material success. Yuehong’s ambition drives her to accept Tang’s proposal to marry, but Chunhua distrusts Tang and refuses to back Yuehong’s plans. Behind the scenes, Tang keeps a wife as a mistress, a detail that foreshadows the moral collapse of certain feudal and capitalist temptations. The turning point comes when Chunhua witnesses Shang Shuihua, Tang’s former lover, commit suicide, an event that catalyzes Chunhua’s politicization and marks the “collapse of the old order” in the eyes of the film’s interpretive framework.

Motivated by this tragedy, Chunhua partners with Jiang Bo, a communist journalist and investigator of the death, Gao Fang. Jiang Bo urges Chunhua to embrace a “progressive” path, guiding her to reimagine the troupe’s repertoire to educate audiences about truth and social justice. Chunhua begins staging works that carry political weight, including a bold adaptation of Lu Xun’s The New Year Sacrifice, and the troupe’s productions are soon banned by the authorities. The newly politicized art becomes a target of repression, as Tang mobilizes to ruin Chunhua’s reputation and maintains his hold over Yuehong through coercion and manipulation. A’Xin is drawn into a lawsuit that attempts to curb Chunhua’s influence, while Yuehong is coerced into testifying against her sister, only to faint at a critical moment in court, underscoring the fractures within their alliance.

The film’s timeline moves toward a watershed moment: the founding of the People’s Republic of China. By 1950, Chunhua prepares to perform The White-Haired Girl for rural audiences in Zhejiang, a decision that aligns her art with the state’s new revolutionary propaganda. Tang has fled to Taiwan with the Kuomintang cohort, and Yuehong is left in Shaoxing, overwhelmed by shame and renouncing her former life. Yet, the sisters’ relationship endures in memory, and they share a tearful reunion near a quay, a moment that crystallizes the film’s central tension between personal ambition and collective ideological duty. Yuehong, chastened by the experience, vows to walk the “correct” path, while Chunhua commits her life to revolutionary operas, embracing a role that transcends individual success. Their decision to continue performing The White-Haired Girl becomes a symbol of art’s responsibility to serve the revolution.

Throughout its narrative arc, the film situates personal choices within the broader currents of Chinese history, from patriarchy and economic exploitation to war, regime suppression, and the rise of socialist ideals. It presents a complex tableau of women navigating talent, desire, and political awakening, where friendships are tested, loyalties shift, and art becomes a field of struggle as much as it is a vehicle for self-expression. The work juxtaposes Chunhua’s unwavering revolutionary zeal with Yuehong’s initial attraction to status and security, ultimately arguing for a collectivist, state-aligned vision of cultural production. The final image—two sisters bound by blood and history, choosing distinct but interwoven paths—frames the film’s assertion that art must align with social transformation, even as it preserves the personal histories that shaped those transformative choices.

Last Updated: October 09, 2025 at 09:33

Explore Movie Threads

Discover curated groups of movies connected by mood, themes, and story style. Browse collections built around emotion, atmosphere, and narrative focus to easily find films that match what you feel like watching right now.

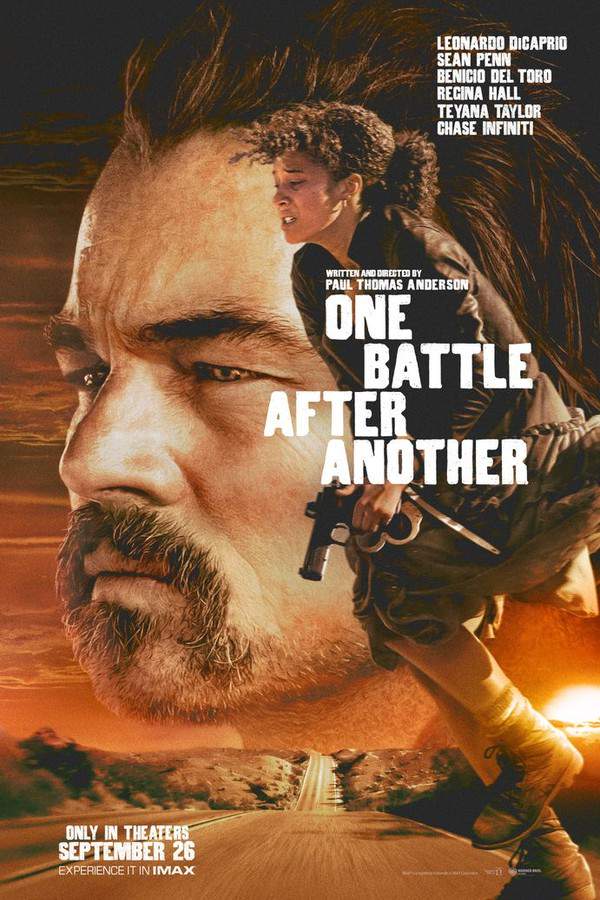

Films about Art and Revolution like Two Stage Sisters

Stories of artists and creators whose work becomes a battleground for political ideologies.If you were captivated by the story of Chunhua and Yuehong in Two Stage Sisters, explore these other movies about artists navigating political turmoil. These dramas delve into how personal creativity collides with collective ideologies, forcing difficult choices between artistic integrity and political survival.

Narrative Summary

The narrative typically follows an artist or creative group whose work gains political significance during a time of revolution or social change. Their personal journey becomes intertwined with the larger historical narrative, forcing them to choose between their artistic vision, personal loyalties, and the demands of the new political order, often resulting in internal conflict and external pressure.

Why These Movies?

These films are grouped together because they share a core conflict: the tension between individual artistic expression and the collective demands of a political movement. They feature a heavy emotional weight, complex character arcs set against historical backdrops, and a tone that is serious and reflective, focusing on the sacrifices made when art becomes propaganda.

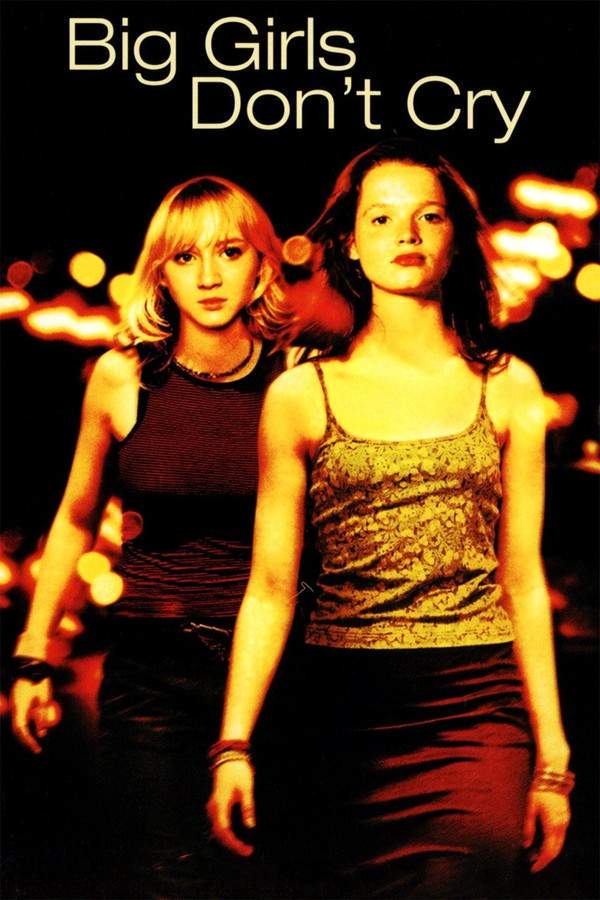

Movies About Friendships Torn by Politics like Two Stage Sisters

Intimate bonds tested and broken by diverging political beliefs and historical forces.For viewers moved by the separation of Chunhua and Yuehong in Two Stage Sisters, this collection features powerful stories of friendships fractured by political beliefs. These films capture the bittersweet pain of personal connections being sacrificed on the altar of ideology, often set against a backdrop of significant historical events.

Narrative Summary

The narrative pattern revolves around a central, strong relationship that is established before a major political or social conflict. As the external pressures mount, the characters' paths diverge based on their beliefs, loyalties, or survival instincts. The story explores the painful process of estrangement, culminating in a reunion or reckoning that highlights the enduring personal loss amidst broader historical 'victories'.

Why These Movies?

These movies are united by their focus on the micro-level human cost of macro-level political events. They share a bittersweet or tragic ending feel, a high emotional weight derived from broken bonds, and a steady pacing that allows the rift between characters to develop organically and painfully over time.

Unlock the Full Story of Two Stage Sisters

Don't stop at just watching — explore Two Stage Sisters in full detail. From the complete plot summary and scene-by-scene timeline to character breakdowns, thematic analysis, and a deep dive into the ending — every page helps you truly understand what Two Stage Sisters is all about. Plus, discover what's next after the movie.

Two Stage Sisters Timeline

Track the full timeline of Two Stage Sisters with every major event arranged chronologically. Perfect for decoding non-linear storytelling, flashbacks, or parallel narratives with a clear scene-by-scene breakdown.

Characters, Settings & Themes in Two Stage Sisters

Discover the characters, locations, and core themes that shape Two Stage Sisters. Get insights into symbolic elements, setting significance, and deeper narrative meaning — ideal for thematic analysis and movie breakdowns.

Two Stage Sisters Spoiler-Free Summary

Get a quick, spoiler-free overview of Two Stage Sisters that covers the main plot points and key details without revealing any major twists or spoilers. Perfect for those who want to know what to expect before diving in.

More About Two Stage Sisters

Visit What's After the Movie to explore more about Two Stage Sisters: box office results, cast and crew info, production details, post-credit scenes, and external links — all in one place for movie fans and researchers.

Similar Movies to Two Stage Sisters

Discover movies like Two Stage Sisters that share similar genres, themes, and storytelling elements. Whether you’re drawn to the atmosphere, character arcs, or plot structure, these curated recommendations will help you explore more films you’ll love.

Explore More About Movie Two Stage Sisters

Two Stage Sisters (1964) Scene-by-Scene Movie Timeline

Two Stage Sisters (1964) Movie Characters, Themes & Settings

Two Stage Sisters (1964) Spoiler-Free Summary & Key Flow

Movies Like Two Stage Sisters – Similar Titles You’ll Enjoy

Pavilion of Women (2001) Movie Recap & Themes

To Live to Sing (2019) Spoiler-Packed Plot Recap

881 (2007) Movie Recap & Themes

The Twin Bracelets (1991) Film Overview & Timeline

Center Stage (1991) Detailed Story Recap

Peking Opera Blues (1986) Movie Recap & Themes

Backstage (2021) Full Summary & Key Details

Three Sisters (1970) Ending Explained & Film Insights

Stand Up, Sisters! (1951) Film Overview & Timeline

Twin Sisters (1934) Plot Summary & Ending Explained

The Soong Sisters (1997) Detailed Story Recap

Sisters of the Gion (1936) Story Summary & Characters

New Women (1935) Spoiler-Packed Plot Recap

Hong Kong Nocturne (1967) Story Summary & Characters

Off the Stage (2022) Full Movie Breakdown