The Great Sinner

Year: 1949

Runtime: 110 mins

Language: English

Director: Robert Siodmak

A great star for every role in a great drama A young man succumbs to gambling fever.

Warning: spoilers below!

Haven’t seen The Great Sinner yet? This summary contains major spoilers. Bookmark the page, watch the movie, and come back for the full breakdown. If you're ready, scroll on and relive the story!

The Great Sinner (1949) – Full Plot Summary & Ending Explained

Read the complete plot breakdown of The Great Sinner (1949), including all key story events, major twists, and the ending explained in detail. Discover what really happened—and what it all means.

On the film’s opening, set in the 1860s Wiesbaden, a storm tears through a shabby attic where Gregory Peck as Fedya lies on a bed, the pages of a manuscript scattering through the air. A woman—later revealed to be Pauline Ostrovsky, played by Ava Gardner—enters, closes the windows, and regards Fedya with a quiet, almost tender concern. She notices that the fluttering pages form a memoir Fedya has been writing, and this discovery sets the stage for a long, reflective journey that unfolds as an extended flashback, sometimes carried by Fedya’s own voice. The atmosphere is intimate, almost claustrophobic, as the storm outside mirrors the storm of motives and temptations swirling inside the story.

Fedya’s tale travels back to a chance encounter on a train from Moscow toward Paris, where he is a writer seeking meaning and the thrill of another kind of truth. It’s on this journey that he meets Pauline, who occupies her travel time with solitaire, calm and focused even as life’s roulette wheel spins around her. Intrigued and drawn to her, Fedya disembarks with her at Wiesbaden and follows her to a casino, where he discovers that Pauline shares a long, unwelcome history with gambling. Her father, General Ostrovsky, is a formidable presence at the casino, a man whose wealth and power are tightly wound with the family’s gambling world. The General’s demeanor—unfazed by the crisis his wealth creates for others—pulls Fedya into a study of addiction, a preoccupation that soon consumes more than just Pauline’s past or the ostentatious displays of fortune.

In this casino-filled landscape, a man named Aristide Pitard emerges—a seasoned thief and compulsive gambler who has his own uneasy code. Frank Morgan embodies Pitard, who claims Fedya’s winnings with a quick, practiced grin. Fedya, moved by pity and curiosity, offers Pitard money to leave the city, hoping to buffer the world from Pitard’s destructive tendencies. But Pitard refuses to walk away. He uses the money to gamble again, and after a tense, inexorable losing streak, he shoots himself in a blaze of desperation. Before his death, Pitard passes Fedya a pawn ticket and asks him to redeem it and return a certain item to its rightful owner, a request that will pull Fedya deeper into the moral maze of debt and obligation. When Fedya retrieves the pledged object, he discovers that the pawned article is a religious medal—and, to his growing astonishment, it belongs to Pauline herself.

Love enters the equation with a profound, aching force. Fedya’s feelings for Pauline deepen as he learns more about her past, and he discovers a cautious tenderness beneath her outward resilience. Yet the road to a possible union is obstructed by a stark truth: Pauline is pledged to Armand de Glasse, a wealthy and ruthless casino owner who exerts immense control over her life through the weight of debt and arrangement. Melvyn Douglas brings Armand’s cold charisma to life, a man whose affluence and power are weapons as easily wielded as charm. Fedya’s response is not to walk away, but to become part of the very machine he set out to study. He decides to gamble himself, hoping to earn enough money to clear the General Ostrovsky’s debts that threaten Pauline’s autonomy and happiness.

What follows is a perilous ascent and rapid descent into gambling obsession. Fedya’s luck appears almost magical at first as he rides a spectacular winning streak at roulette, his early success fueling his belief that the world can be rearranged by sheer luck and cleverness. The winnings he accumulates are meant to cover the General’s enormous debt—about 200,000 marks—and to secure Pauline’s future from a merciless arrangement. But the euphoria proves temporary. Armand’s insistence on redeeming the General’s marker becomes a stubborn bottleneck, and Fedya’s fortune begins to sag as his mind fixates on “lucky numbers” that seem to haunt him everywhere. The once-glittering casino glow fades into a haze of risk, fear, and escalating bets that threaten to swallow him whole.

The nadir comes in the private Baccarat rooms where Fedya, driven to recoup losses, borrows against his future earnings to keep playing. The casino’s merciless atmosphere—its velvet darkness and gleaming chips—becomes a laboratory of temptation, and Fedya’s discipline breaks down under pressure. He loses what remains, including the collateral that should have steadied him against the fall. Armand, unscrupulous as ever, is only too happy to take everything Fedya has left, further entwining debt, desire, and despair. In the wake of these losses, Fedya clings to whatever remains, pawning his few possessions in a desperate bid to salvage the situation, only to be overtaken by the crushing gravity of his own addiction.

Despair deepens into a hallucinatory turn when Aristide—appearing in a spectral form—hands Fedya a gun and an unthinkable prompt to end it all. In this haze, Pauline reappears, and Fedya, in a frenzy of fear and longing, grabs her religious medal and tries to sell it to Emma Getzel, the pawnbroker who later proves crucial to the narrative’s moral texture. Emma Getzel, played by Agnes Moorehead, refuses to buy the medal, underscoring the medal’s significance beyond mere wealth or possession. Fedya’s violence nearly erupts in this moment, but the act collapses into a faint, a collapse into consciousness that pauses the downward spiral just long enough for a new reckoning to begin.

Meanwhile, Pauline’s grandmother—drawn with the weight of her own loss and the cruel unpredictability of fortune—arrives in the story’s orbit. The General Ostrovsky, a man whose life has hinged on the rhythm of baccarat and debt, moves this older generation into the casino’s brutal dance, with Pauline’s grandmother ultimately meeting a tragic end at the gaming table after draining a fortune. This tragedy compounds the moral questions at the heart of the film: What is the price of desire? How do love, loyalty, and duty fare when economics and addiction pull in opposite directions?

In the film’s final stretch, Fedya completes his manuscript—a confession and a meditation on gambling’s obsessions, written with the clarity that only a man who has walked through the flames of recklessness can command. The act of writing becomes a form of redemption, a way to distill experience into meaning. And in the most crucial, intimate turn, Pauline forgives Fedya for his rapturous plunge into risk and obsession. The memory of their shared longing—fueled by the medal, the debts, the memoir, and the gamble—lives on as the story’s quiet, unresolved mercy. The film ends not with a dramatic rescue or a clean victory, but with a fragile, human pause: forgiveness, memory, and a manuscript that seeks to answer the question of whether gambling’s siren song can ever be written away.

Last Updated: October 09, 2025 at 11:26

Explore Movie Threads

Discover curated groups of movies connected by mood, themes, and story style. Browse collections built around emotion, atmosphere, and narrative focus to easily find films that match what you feel like watching right now.

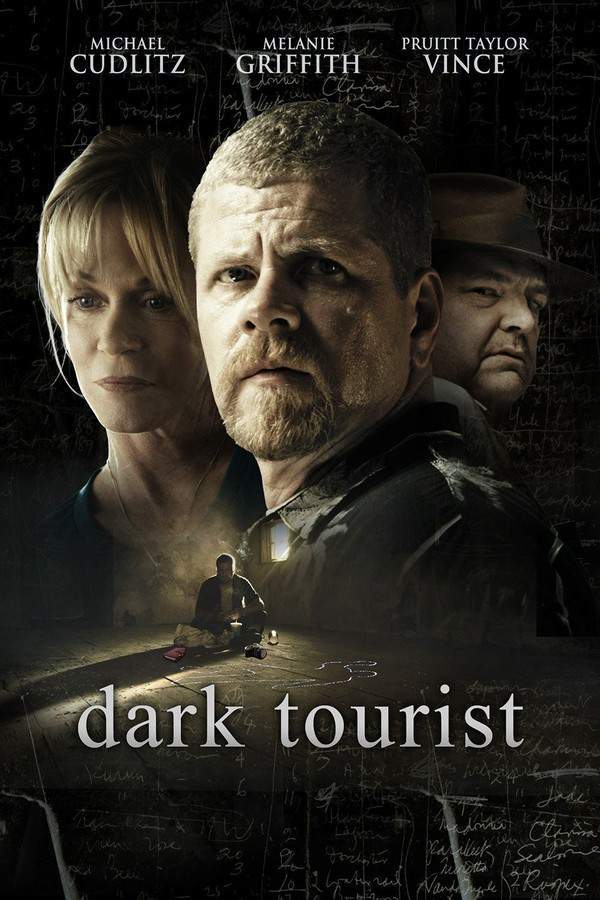

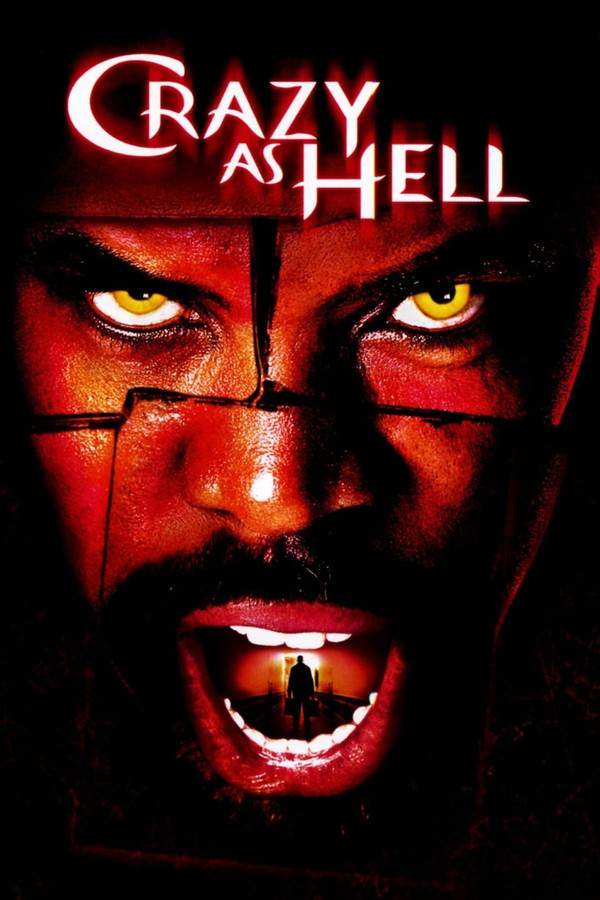

Obsessive drama movies like The Great Sinner

Stories where a single fixation leads to complete moral and financial collapse.For viewers who liked The Great Sinner, this list features movies about obsessive journeys into self-destruction. These similar drama films explore characters gripped by a single, destructive passion, leading to intense psychological struggles and moral crises.

Narrative Summary

The narrative pattern centers on a charismatic or ordinary individual who discovers a potent new interest. This obsession quickly becomes an addiction, eclipsing all other aspects of their life—relationships, finances, and morals—leading to a steep, often irreversible decline into a personal abyss.

Why These Movies?

Movies are grouped here based on their shared focus on a protagonist's psychological unraveling through obsession. They share a dark, intense tone, a steady pacing that builds a sense of inevitability, and a heavy emotional weight stemming from witnessing a tragic character arc.

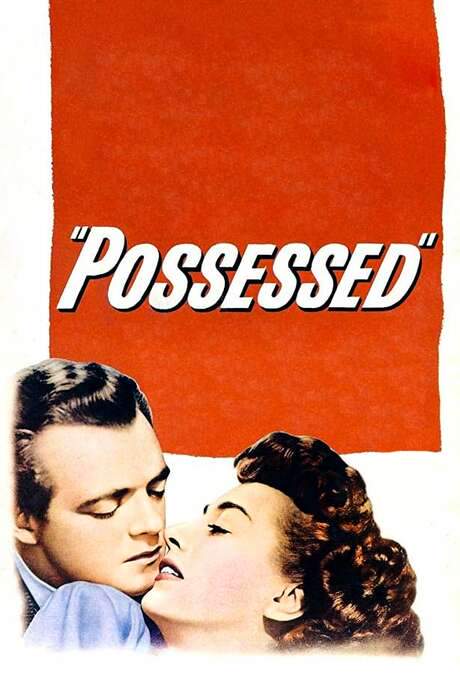

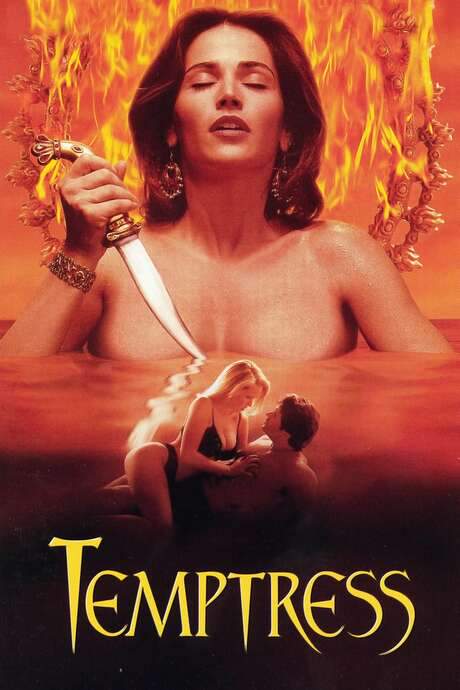

Bittersweet redemption stories like The Great Sinner

Journeys of profound loss that find a sliver of hope, but not without scars.If you enjoyed the moral journey in The Great Sinner, explore these movies about bittersweet redemption. These films feature characters who face the consequences of their actions and find a difficult, uncertain path to salvation, blending heavy drama with a touch of hope.

Narrative Summary

The narrative follows a character through a period of intense moral failure and self-destruction, culminating in a crisis that leaves them with nothing. The story then explores a hard-won, often unconventional path to atonement, resulting in an ending that is neither purely happy nor bleak, but thoughtfully bittersweet.

Why These Movies?

These films are united by their exploration of redemption after tragedy. They balance a dark tone with a glimmer of hope, feature a heavy emotional journey, and consistently deliver a bittersweet resolution that feels earned rather than facile.

Unlock the Full Story of The Great Sinner

Don't stop at just watching — explore The Great Sinner in full detail. From the complete plot summary and scene-by-scene timeline to character breakdowns, thematic analysis, and a deep dive into the ending — every page helps you truly understand what The Great Sinner is all about. Plus, discover what's next after the movie.

The Great Sinner Timeline

Track the full timeline of The Great Sinner with every major event arranged chronologically. Perfect for decoding non-linear storytelling, flashbacks, or parallel narratives with a clear scene-by-scene breakdown.

Characters, Settings & Themes in The Great Sinner

Discover the characters, locations, and core themes that shape The Great Sinner. Get insights into symbolic elements, setting significance, and deeper narrative meaning — ideal for thematic analysis and movie breakdowns.

The Great Sinner Spoiler-Free Summary

Get a quick, spoiler-free overview of The Great Sinner that covers the main plot points and key details without revealing any major twists or spoilers. Perfect for those who want to know what to expect before diving in.

More About The Great Sinner

Visit What's After the Movie to explore more about The Great Sinner: box office results, cast and crew info, production details, post-credit scenes, and external links — all in one place for movie fans and researchers.

Similar Movies to The Great Sinner

Discover movies like The Great Sinner that share similar genres, themes, and storytelling elements. Whether you’re drawn to the atmosphere, character arcs, or plot structure, these curated recommendations will help you explore more films you’ll love.

Explore More About Movie The Great Sinner

The Great Sinner (1949) Scene-by-Scene Movie Timeline

The Great Sinner (1949) Movie Characters, Themes & Settings

The Great Sinner (1949) Spoiler-Free Summary & Key Flow

Movies Like The Great Sinner – Similar Titles You’ll Enjoy

The Gambler (2014) Complete Plot Breakdown

The Gambler (1974) Story Summary & Characters

His Greatest Gamble (1934) Movie Recap & Themes

Man, Woman and Sin (1927) Full Summary & Key Details

The Great Gambler (1979) Spoiler-Packed Plot Recap

The Big Gamble (1931) Film Overview & Timeline

Bay of Angels (1963) Detailed Story Recap

Gambler’s Choice (1944) Movie Recap & Themes

Smart Money (1931) Complete Plot Breakdown

The Great Game (1934) Ending Explained & Film Insights

Gambling with Souls (1936) Ending Explained & Film Insights

Sinner Take All (1936) Plot Summary & Ending Explained

The Gambler and the Lady (1952) Full Summary & Key Details

The Great Swindle (1971) Complete Plot Breakdown

The Sin Ship (1931) Spoiler-Packed Plot Recap