Divine Words

Year: 1987

Runtime: 107 mins

Language: Spanish

Director: José Luis García Sánchez

Set in early‑20th‑century Galicia, this Valle‑Inclán drama follows the sacristan’s wife, who, desperate to lift her family from poverty, exploits a hydrocephalic child as a sideshow attraction. Her ruthless scheme provokes a fierce clash with her sister‑in‑law, exposing the harsh social realities of the time.

Warning: spoilers below!

Haven’t seen Divine Words yet? This summary contains major spoilers. Bookmark the page, watch the movie, and come back for the full breakdown. If you're ready, scroll on and relive the story!

Divine Words (1987) – Full Plot Summary & Ending Explained

Read the complete plot breakdown of Divine Words (1987), including all key story events, major twists, and the ending explained in detail. Discover what really happened—and what it all means.

In the province of Galicia, circa 1920, the film unfolds in the impoverished village of San Clemente, where religious authority has collapsed into the hands of the sacristan Pedro Gailo, and his young wife Mari Gaila, Ana Belén, endures a brittle, money-fueled marriage. With a hydrocephalus-stricken child under their care, the couple turns the child into a source of income, a bedrock on which Mari Gaila builds a hustler’s life. The power dynamic is stark: Pedro’s outward piety masks a sharp hunger for wealth, while Mari Gaila dances on the edge of moral collapse, her gaze fixed on escape from the village and a life far removed from the prying eyes of San Clemente.

Mari Gaila’s leverage is strengthened by the joint guardianship she shares with her sister-in-law, Marica, Aurora Bautista. The pair navigate a world that rewards audacity, even as it shames vulnerability. Into this precarious ecosystem wanders another beggar, a woman nicknamed “la Tatula,” whose presence signals the arrival of outsiders who can haze the borders between poverty and performance. The figure of Rosa la Tatula, portrayed by Esperanza Roy, embodies the carnival-like blur between need and spectacle that the village culture treats as entertainment.

Driven by a mix of longing and calculation, Mari Gaila ventures toward the nearest city, stepping into a landscape filled with music, markets, and people who move with a confidence she has never known. The city offers her a taste of a wider world—one that jingles with possibility and danger in equal measure. Among the flourishing fairs and the bustling roads, she becomes a magnet for other nomadic beggars and unscrupulous players who are drawn to her new wealth. One such figure is Septimo Miau, Imanol Arias, a handsome outlaw whose presence unsettles the delicate balance Mari has constructed.

A brief, charged flirtation with Septimo Miau pulls Mari Gaila deeper into a life that seems to promise freedom but veers toward risk. She returns to her village not empty-handed but transformed, the town suddenly aware of her wealth and the broader horizons she now claims. The relationship with Septimo rekindles, and the two lovers rekindle their plan to run away together, using the hydrocephalus child as a bizarre, movable exhibit to extract sympathy—and money—from sympathetic crowds. Yet the joy is short-lived. While the lovers compose themselves in a forest, locals feed the child alcohol at a tavern, and the child dies in a tragedy that exposes the fragile seam between charity and exploitation.

Septimo Miau deserts Mari Gaila, leaving her diminished and ill, a shadow of the audacious woman who left San Clemente with stars in her eyes. The sacristan Pedro Gailo, never one to let a tragedy go unutilized for personal gain, seizes on the body of his nephew and stages a grotesque display—the corpse becomes a vehicle for shock and profit, a chilling tableau that underscores the village’s hunger and depravity. The rescue of the lovers comes later, as Rosa la Tatula reappears as a broker of loyalties, and the two lovers meet again in a forest, their passion reignited but now entangled with fear and vengeance.

Caught in the crosscurrents of gossip, judgment, and desperation, Mari Gaila is finally stripped of dignity—naked, spat upon, derided, and stoned by a crowd whose brutal instinct seems to reflect their own losses and resentments. The crowd’s “justice” is interrupted by a chilling liturgy of mercy as Pedro Gailo speaks the Latin phrase, “Let him who is free of sin cast the first stone,” and the crowd disperses, momentarily stupefied by the irony of its own actions. In that moment, the film probes the contradiction at the heart of a community that monologues about virtue while devouring its weakest members.

What follows is a meditation on moral complexity, poverty, and the claustrophobic pressures that drive people to make, and unmake, themselves in a world that rewards cunning over compassion. The story revels in its own ambivalence: Pedro remains, at least outwardly, a saintly figure, offering forgiveness and maintaining a pose of pious authority, while Mari Gaila, burned by accusation and spectacle, emerges as someone too lucid and too fragile to be easily categorized as merely virtuous or immoral. The film closes on a note of sober reflection: a village that has learned too late the cost of its own hypocrisy, a community of downtrodden people who dream of escape but find themselves trapped in a cycle of gossip, hunger, and small, stubborn resentments.

Let him who is free of sin cast the first stone

In this environmental canvas, the characters move through a social ecosystem that is at once intimate and sprawling, a place where every gesture—whether a beggar’s plea, a sacristan’s ledger, or a love affair—carries a weight of consequence. The film is a study in contrasts: the austere, ritualized world of San Clemente versus the riotous, unpredictable pulse of the outside world; a marriage defined by economic necessity, and a romance attempted at the price of public scorn. As the crowd disperses, the narrative lingers on the ambiguous moral weather of the village: the honest and the corrupt, the hurt and the cunning, all caught in a liminal space where the line between virtue and vice is both blurred and perpetually renegotiated. The final image is less a revelation than a question—of how a society chooses to remember its faults, and whether forgiveness can survive the harsh glare of a community that has learned to profit from its own vulnerabilities.

Last Updated: October 09, 2025 at 14:36

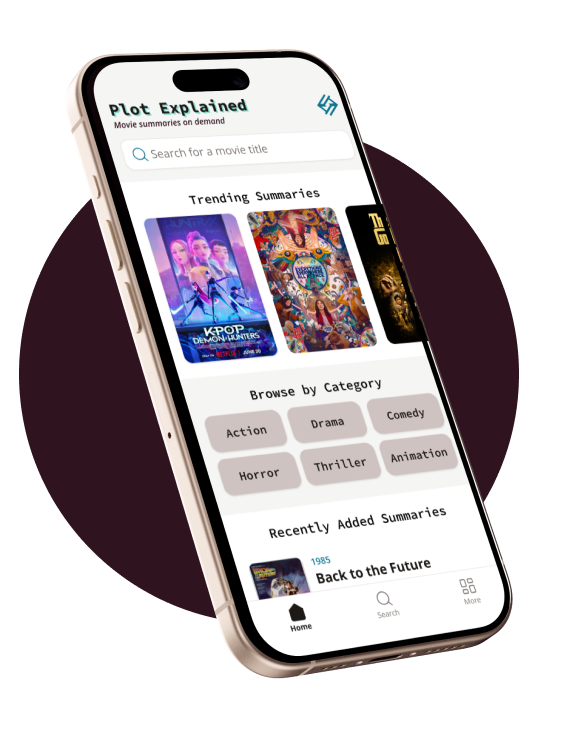

Explore Movie Threads

Discover curated groups of movies connected by mood, themes, and story style. Browse collections built around emotion, atmosphere, and narrative focus to easily find films that match what you feel like watching right now.

Grim Social Realism Movies like Divine Words

Unflinching dramas exposing the moral decay of desperate communities.If you appreciated the stark portrayal of poverty and moral decay in Divine Words, explore these similarly bleak social realism films. This list features movies that depict the harsh realities of life in oppressive communities, focusing on themes of desperation, exploitation, and grim social commentary.

Narrative Summary

Narratives in this thread often follow characters trapped by their socio-economic circumstances, whose desperate attempts to survive lead them into ethical gray areas or outright moral collapse. The conflict typically arises from within the community itself, pitting characters against each other in a struggle for meager resources or dignity, culminating in bleak outcomes that reinforce the cyclical nature of their hardship.

Why These Movies?

These films are grouped together for their shared commitment to a raw, unsentimental depiction of societal ills. They possess a consistently dark tone, heavy emotional weight, and a focus on the psychological impact of poverty and confinement, creating a similarly somber and thought-provoking viewing experience.

Moral Descent Dramas Similar to Divine Words

Character-driven stories where desperation leads to a loss of innocence.For viewers who were captivated by the slow, grim moral collapse in Divine Words, this collection highlights other character-driven dramas about desperate choices. Discover movies that explore how good people can be corrupted by circumstance, featuring steady pacing, dark tones, and emotionally heavy conclusions.

Narrative Summary

The narrative pattern centers on a protagonist who, while not initially evil, is placed under immense pressure. The story follows their step-by-step journey as they rationalize unethical actions, often exploiting others for personal gain. The conflict is internal as much as external, culminating in a tragic loss of self and a bleak ending that serves as the consequence of their choices.

Why These Movies?

These movies share a focus on a specific character arc: the tragic fall from grace. They combine a steady, deliberate pacing that allows the corruption to feel earned with a dark tone and high emotional intensity, making the protagonist's journey into darkness both compelling and horrifying to witness.

Unlock the Full Story of Divine Words

Don't stop at just watching — explore Divine Words in full detail. From the complete plot summary and scene-by-scene timeline to character breakdowns, thematic analysis, and a deep dive into the ending — every page helps you truly understand what Divine Words is all about. Plus, discover what's next after the movie.

Divine Words Timeline

Track the full timeline of Divine Words with every major event arranged chronologically. Perfect for decoding non-linear storytelling, flashbacks, or parallel narratives with a clear scene-by-scene breakdown.

Characters, Settings & Themes in Divine Words

Discover the characters, locations, and core themes that shape Divine Words. Get insights into symbolic elements, setting significance, and deeper narrative meaning — ideal for thematic analysis and movie breakdowns.

Divine Words Spoiler-Free Summary

Get a quick, spoiler-free overview of Divine Words that covers the main plot points and key details without revealing any major twists or spoilers. Perfect for those who want to know what to expect before diving in.

More About Divine Words

Visit What's After the Movie to explore more about Divine Words: box office results, cast and crew info, production details, post-credit scenes, and external links — all in one place for movie fans and researchers.

Similar Movies to Divine Words

Discover movies like Divine Words that share similar genres, themes, and storytelling elements. Whether you’re drawn to the atmosphere, character arcs, or plot structure, these curated recommendations will help you explore more films you’ll love.

Explore More About Movie Divine Words

Divine Words (1987) Scene-by-Scene Movie Timeline

Divine Words (1987) Movie Characters, Themes & Settings

Divine Words (1987) Spoiler-Free Summary & Key Flow

Movies Like Divine Words – Similar Titles You’ll Enjoy

Divine Love (2020) Spoiler-Packed Plot Recap

The Divine Order (2017) Full Summary & Key Details

Divine Access (2016) Detailed Story Recap

Day of Wrath (2006) Movie Recap & Themes

Bellas durmientes (2001) Story Summary & Characters

Don de Dios (2005) Plot Summary & Ending Explained

The Divine Comedy (1991) Full Summary & Key Details

Beyond the Walls (1985) Ending Explained & Film Insights

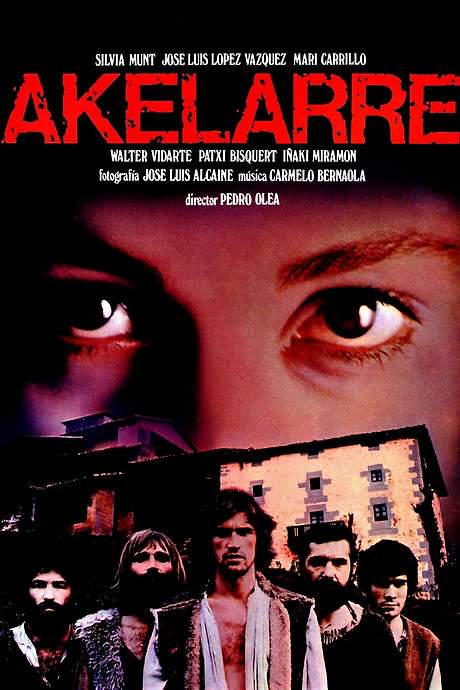

Akelarre (1984) Ending Explained & Film Insights

Blood and Passion (1976) Full Summary & Key Details

The Divine Woman (1928) Complete Plot Breakdown

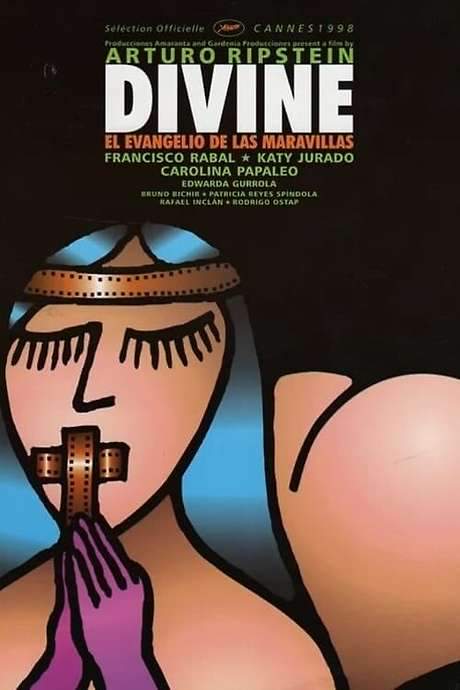

Divine (1998) Spoiler-Packed Plot Recap

Divine Confusion (2008) Complete Plot Breakdown

Suspiros de España (y Portugal) (1995) Story Summary & Characters

Doña Diabla (1950) Ending Explained & Film Insights

-gv2b_HtyqJrUgw.jpg)