The Canterbury Tales

Year: 1972

Runtime: 111 mins

Language: Italian

From the creators of “Decameron”, this lively film presents Geoffrey Chaucer’s most risqué tales of medieval England. It intersperses brief dramatized glimpses of Chaucer himself penning his famous work with vivid re‑enactments of several bawdy stories, capturing the humor and romance of the era.

Warning: spoilers below!

Haven’t seen The Canterbury Tales yet? This summary contains major spoilers. Bookmark the page, watch the movie, and come back for the full breakdown. If you're ready, scroll on and relive the story!

The Canterbury Tales (1972) – Full Plot Summary & Ending Explained

Read the complete plot breakdown of The Canterbury Tales (1972), including all key story events, major twists, and the ending explained in detail. Discover what really happened—and what it all means.

Set in medieval England, the film weaves together the daily lives of peasants, nobles, clergy, and even demons, while punctuating the narrative with brief glimpses into Geoffrey Chaucer’s world and the seeds of the Canterbury Tales. The frame is anchored by Chaucer, Pier Paolo Pasolini, as the storyteller who gathers travelers at the Tabard inn and, between interruptions and exchanges, opens his book to record a sequence of interlinked, stand-alone tales rather than a single mosaic of pilgrim-led stories.

The Prologue establishes the ensemble as the Gaudy Roadshow of the era—at the Tabard inn, the travelers chat, tease, and trade jokes as a ballad called Ould Piper fills the air. The heavy, tattooed man Daggers of the past looms as a visual contrast and foreshadowing, and the group’s dynamic sets the tone for the immediately following tales. The Prologue, framed by Chaucer’s presence, introduces the idea that the later episodes will be relayed and woven with a author’s eye, a meta-sense of storytelling that becomes the film’s throughline.

First Tale (The Merchant’s Tale)

Sir January, [Hugh Griffith], a weary and aging aristocrat, decides to wed May, a youthful woman who harbors real romantic interest in Damian. After their marriage, January suddenly becomes blind, and clings to May’s wrist for solace while she toys with her freedom and her forbidden love. May crafts a discreet path to her beloved in a private garden, aided by a key, and the two lovers improvise a plan to indulge themselves amid trees and flowering branches. The garden becomes a stage where a godlike Pluto [Giuseppe Arrigio] silently watches the lovers’ maneuverings, and where May’s scheming is tempered by the timely intervention of Persephone, who provides a calm rationalization for January’s wrath. Just as his sight returns, he briefly glimpses May and her lover in the act, but the goddess Persephone helps smooth things over with a few deft excuses, and the couple walks away reconciled, their marriage surviving the moment of crisis.

Second Tale (The Friar’s Tale)

A vendor witnesses a summons-related sting: a summoner and two men are caught in sodomy, and a bribe buys one escape while a second man meets a grimmer fate on a griddle. The vendor hawks his wares as the crowd watches, and afterward teams up with the summoner, revealing a shared appetite for profit. The old woman who is accused of wrongdoing tries to bargain her way out with bribes, but the summoner’s false charges meet their match when the old woman curses him to the Devil if he does not repent. The exchange tests the boundaries between crime, punishment, and the power of a single curse, while the Devil’s arrival underscores the moral economy of the tale.

Third Tale (The Cook’s Tale)

The travelers at the Tabard Inn fall quiet as Chaucer resumes recording stories, beginning with Perkin, a Pip-Pip-esque rogue who drags trouble behind him like a cloud. Perkin steals from passersby, causes chaos at a wedding, and finds himself pursued by the law, only to escape in a dramatic turn that leads back home to more scolding from family and the same old hunger. Perkin’s antics—from crashing weddings to pilfering coins and ending up in the stocks while singing a traditional tune—paint a portrait of a brisk, reckless street-smart street performer whose fate reflects the era’s rough edge.

Fourth Tale (The Miller’s Tale)

Nicholas, a clever young student, moves into the home of John, a stout carpenter, and quickly becomes entangled with John’s young wife, Alison. Alison quietly resents her husband and enjoys Nicholas’s attention, while Absolon and his friend Martin pursue Alison as well, staging a serenade that disturbs the household. Nicholas pretends to be in a holy trance to lure John away, proposing that they await a flood by suspending themselves in buckets from the ceiling. The couple’s ruse succeeds—at least temporarily—until the prank escalates: Alison flirts, Absolon comes back with a hot poker, and the mischief culminates in a double deception that leaves Nicholas urgently crying for water as John discovers the ruse and crashes to the floor, a comic catastrophe that echoes the Miller’s own worldly cunning.

Fifth Tale (The Wife of Bath’s Prologue)

In Bath, a middle-aged wife who has already married multiple times becomes enamored with a young student named Jenkin [Tom Baker]. During an improvised Obby Oss celebration, she arranges to meet him, and in a swift romance, she convinces him to marry her rather than his previous vows. The Wife of Bath’s vibrant personality shines in a scene where she reads aloud from a book condemning women’s evils, only to topple the book over and continue to court her new husband. Her fifth marriage accelerates as she escorts the celebration into another wing of the cathedral, and upon her wedding night she mocks conventional moral lecturing by biting her husband’s nose as a rebuke to those who would dictate her life. The episode is voiced through the Wife of Bath’s Prologue, which informs her later tale’s perspective on power, marriage, and female agency.

Sixth Tale (The Reeve’s Tale)

In Cambridge, a manciple falls ill, and two students—Alan and John—step in to run the mill’s duties. The Miller—Simkin the Miller—outsmarts them by releasing their horse and swapping their flour for bran, a scheme that tests both wit and appetite. The students stay the night, sharing a pallet with the Miller and his wife, and the nocturnal mischief unfolds as Alan admits to his affair with Molly, the Miller’s daughter, while John faces a similar temptation. When the Miller’s wife rises to relieve herself and stumbles, John seizes the moment to trick the Miller by moving the crib, causing the Miller to wake to a different romantic arrangement. The two scholars depart with their flour as Molly laments the deception, a scene that blends practical jokes with a cautionary note about trust and vulnerability.

Seventh Tale (The Pardoner’s Tale)

Chaucer’s frame returns with a quiet intensity as the Pardoner steers the narrative toward Death’s mischief in Flanders. Four young men carousing in a brothel encounter Death in various forms and decide to hunt him down. They meet an old man who directs them toward a nearby oak tree where they discover treasure instead of Death. Two youths remain by the tree while a third heads to town for wine, returning with three casks, two of which are poisoned. In a swift turn of greed, the trio betrays one another, and the survivors fall to the same fate they sought to punish, a fable about the corrosive power of avarice and betrayal.

Eighth Tale (The Summoner’s Tale)

In a final comic sting, a gluttonous friar attempts to wring donations from a bedridden parishioner, who offers a twist: he will share a treasured possession with all the friars if the friar distributes it fairly. The parishioner teases the friar with a riddle about a treasure that lies beneath him, and when the friar tests his will, the bedridden man delivers a crude fart that sets in motion a vision in which an angel guides the friar to an underworld where corrupt friars are expelled. This climactic sequence—part parody, part moral fable—draws on the Summoner’s prologue and folds the theme of hypocrisy into the final tale.

Epilogue (Chaucer’s Retraction)

The pilgrims arrive at Canterbury Cathedral as Chaucer, at home, writes in translation: “Here ends the Canterbury Tales, told only for the pleasure of telling them. Amen.” The film’s Epilogue diverges from the original text, presenting Pasolini’s Chaucer as unabashed about sexuality and ready to confess the tales’ ribaldry rather than urging restraint. The result is a closing mood that embraces the tales’ audacious spirit while leaving a personal mark on how the stories might be read as a whole.

Here ends the Canterbury Tales, told only for the pleasure of telling them. Amen

Last Updated: October 09, 2025 at 12:37

Explore Movie Threads

Discover curated groups of movies connected by mood, themes, and story style. Browse collections built around emotion, atmosphere, and narrative focus to easily find films that match what you feel like watching right now.

Bawdy historical comedies like The Canterbury Tales

Historically-set comedies that find humor in earthy human desires and societal hypocrisy.If you liked the earthy humor and medieval satire of The Canterbury Tales, explore more movies like it. This collection features ribald comedies set in the past that use historical settings to playfully expose human desire, social hypocrisy, and comedic deception.

Narrative Summary

Narratives in this thread often involve interconnected tales or a central comedic premise where characters navigate societal rules through cunning, seduction, and trickery. The plots are driven by human desires and the humorous consequences of attempting to subvert or exploit the norms of their time, often ending with ironic twists rather than clear moral lessons.

Why These Movies?

Movies are grouped here for their shared commitment to historical satire through a light, comedic, and often bawdy lens. They share a playful tone, a focus on human folly over heroism, and a desire to entertain by holding a distorted, humorous mirror to the past.

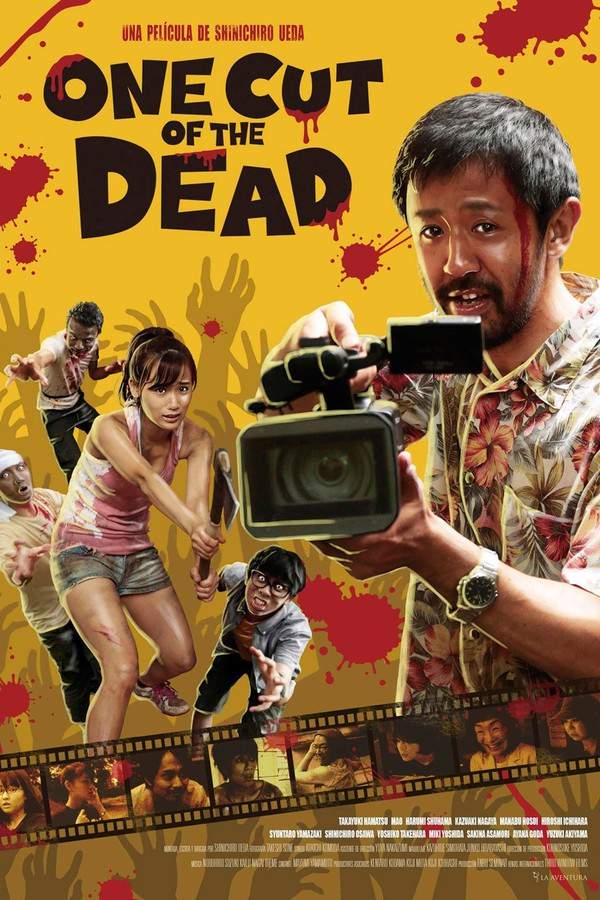

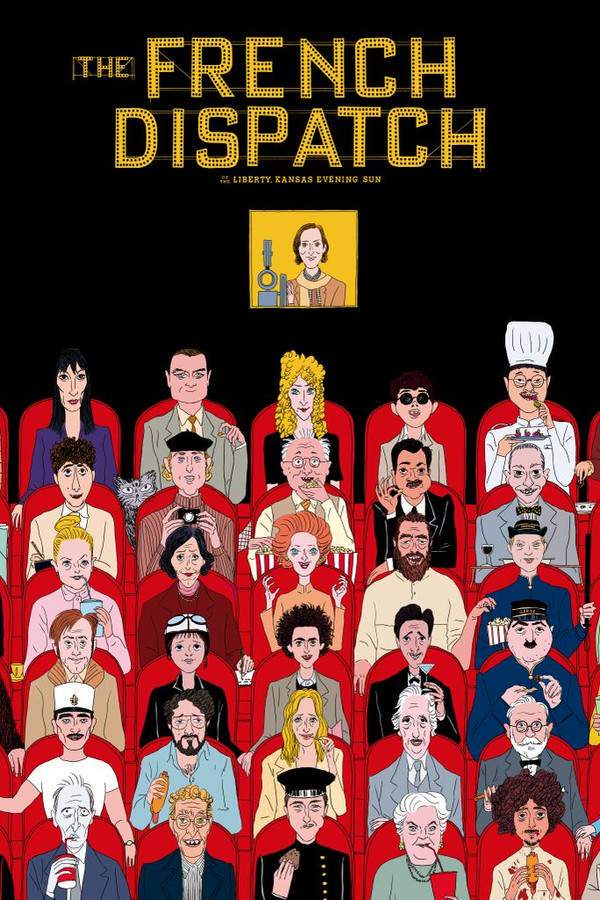

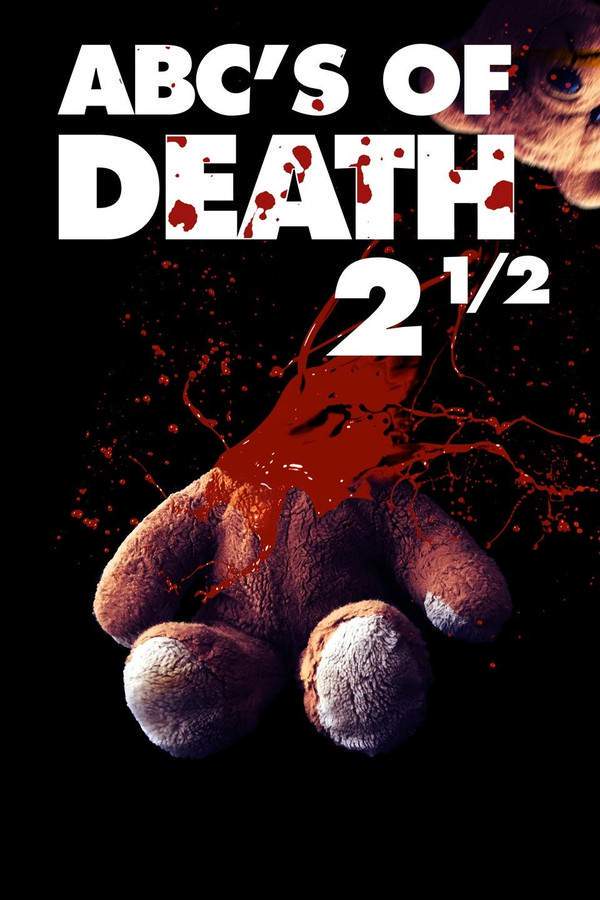

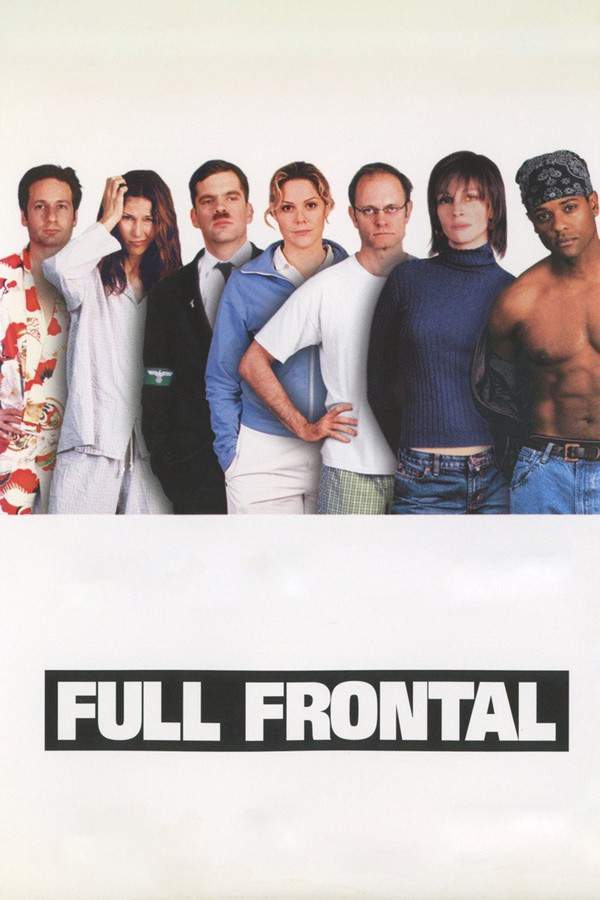

Movies with framed narratives like The Canterbury Tales

Films that weave multiple self-contained tales into a larger narrative frame.Fans of the storytelling structure in The Canterbury Tales will enjoy these other movies with framed narratives. Discover similar films where a central premise connects multiple vignettes or tales, creating a complex and engaging tapestry of stories that play off one another.

Narrative Summary

The narrative pattern involves a primary story that sets the stage for a collection of secondary tales. These embedded stories can vary in tone, genre, and pacing but are unified by a common theme or purpose introduced by the frame. The overall arc is less about a single character's journey and more about the collective impact and thematic resonance of the assembled stories.

Why These Movies?

These films are grouped by their distinctive and complex narrative architecture. They share a 'variable' pacing that shifts between frame and tale, and they offer a viewing experience focused on thematic exploration and structural playfulness rather than a single linear plot.

Unlock the Full Story of The Canterbury Tales

Don't stop at just watching — explore The Canterbury Tales in full detail. From the complete plot summary and scene-by-scene timeline to character breakdowns, thematic analysis, and a deep dive into the ending — every page helps you truly understand what The Canterbury Tales is all about. Plus, discover what's next after the movie.

The Canterbury Tales Timeline

Track the full timeline of The Canterbury Tales with every major event arranged chronologically. Perfect for decoding non-linear storytelling, flashbacks, or parallel narratives with a clear scene-by-scene breakdown.

Characters, Settings & Themes in The Canterbury Tales

Discover the characters, locations, and core themes that shape The Canterbury Tales. Get insights into symbolic elements, setting significance, and deeper narrative meaning — ideal for thematic analysis and movie breakdowns.

The Canterbury Tales Spoiler-Free Summary

Get a quick, spoiler-free overview of The Canterbury Tales that covers the main plot points and key details without revealing any major twists or spoilers. Perfect for those who want to know what to expect before diving in.

More About The Canterbury Tales

Visit What's After the Movie to explore more about The Canterbury Tales: box office results, cast and crew info, production details, post-credit scenes, and external links — all in one place for movie fans and researchers.

Similar Movies to The Canterbury Tales

Discover movies like The Canterbury Tales that share similar genres, themes, and storytelling elements. Whether you’re drawn to the atmosphere, character arcs, or plot structure, these curated recommendations will help you explore more films you’ll love.

Explore More About Movie The Canterbury Tales

The Canterbury Tales (1972) Scene-by-Scene Movie Timeline

The Canterbury Tales (1972) Movie Characters, Themes & Settings

The Canterbury Tales (1972) Spoiler-Free Summary & Key Flow

Movies Like The Canterbury Tales – Similar Titles You’ll Enjoy

A Knight's Tale (2001) Full Summary & Key Details

Virgin Territory (2007) Ending Explained & Film Insights

Naughty Nun (1972) Spoiler-Packed Plot Recap

Tales of Canterbury (1973) Plot Summary & Ending Explained

The Thousand and One Nights of Boccaccio in Canterbury (1973) Film Overview & Timeline

On My Way to the Crusades, I Met a Girl Who… (1967) Full Summary & Key Details

Tales of Erotica (1996) Movie Recap & Themes

What? (1972) Ending Explained & Film Insights

Tales of Erotica (1972) Ending Explained & Film Insights

More Sexy Canterbury Tales (1972) Complete Plot Breakdown

My Tale Is Hot (1964) Story Summary & Characters

Boccaccio ’70 (1962) Plot Summary & Ending Explained

The Sexbury Tales (1973) Complete Plot Breakdown

The Decameron (1000) Film Overview & Timeline

The Decameron (1971) Detailed Story Recap